Upon examining a figure carving by a student, the master carver noted that, while the detail was fairly well done, the carving was “still in the block."

He explained that some beginners are so preoccupied with quickly getting to the details that they don't give enough attention to fully shaping the figure itself; still others have a fear of removing too much wood with the result that they don't take away enough.

In each case, the outcome is a carving "still in the block." In much of his own work, the master carver took care that none of its planes were parallel to those of the original block of wood.

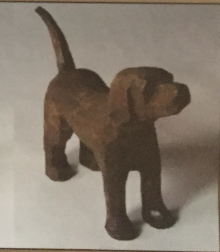

On the most fundamental level, getting a figure out of the block is accomplished by completely shaping the forms—"getting rid of the corners.” For example, real dogs don't have flat sides, but many amateur carvings of dogs do have flat sides.

The fear of taking too much wood away leaves the carving still with the corners and the flat sides of the original block of wood. It's not only an issue with “realistic" carving. An incompletely carved caricature will often have flat sides, still reflective of the original block of wood.

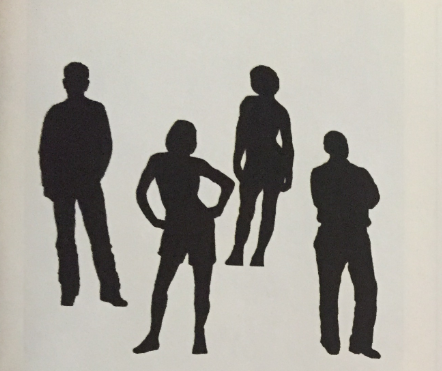

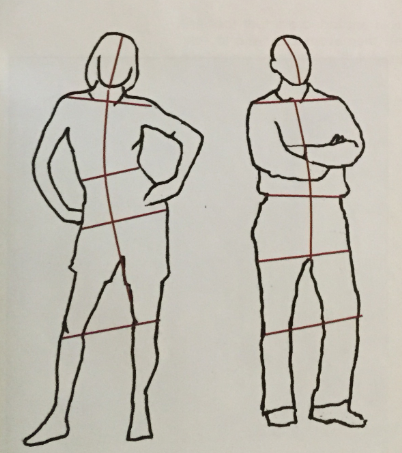

On a more advanced level, getting the figure out of the block is accomplished by turning the pose in some way. such as moving one leg forward or shifting the weight (or both) so that the shoulders are tilted and the hips are turned, resulting in a more dynamic composition.

Except when at attention, it is seldom that a person stands with feet, arms, hips, and shoulders parallel. Most of the time, the weight is shifted to one foot or the other, and the hips and shoulders are tilted to compensate for the weight shift. Creating a more dynamic pose in the figure can make for a more interesting artistic composition as well.

It’s a good idea to take some time to observe the postures of the people around you, or check pictures of people who are standing. You will notice that few of them stand with their limbs, shoulders, and hips parallel.

Most of the time the weight is shifted and the hips are tilted. balanced by the opposite tilting of the shoulders. One foot is often ahead of the other and the arms are in an informal position.

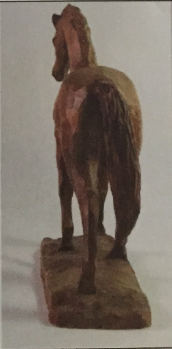

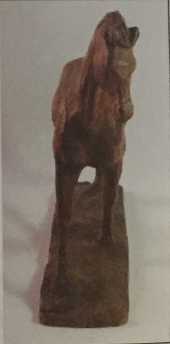

A beginner's carving will often have flat sides and features parallel to the original block of wood, with more complete modeling and turning the head and tail, the dog is nearly “out of the block."

People seldom stand with shoulders and hips parallel. Most of the time the weight is shifted to one leg or the other, and the body is tilted to balance the masses.

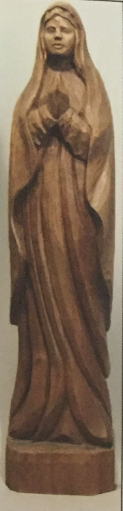

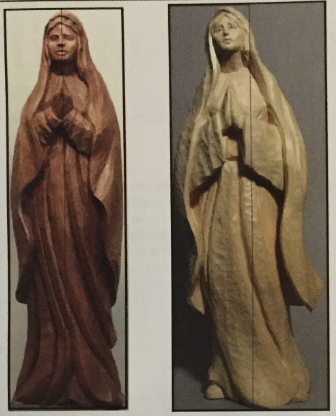

In this carving of the Madonna, the detail shows movement but the figure itself is still in the block.

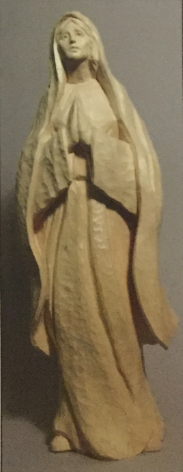

This Madonna carving, however, is out of the block, since none of the planes of the figure are parallel to the original block of wood. Also, the posture is shifted to take the head, shoulders, and hips out of parallel with the edges of the block.

Usually, the hips tilt the opposite way of the shoulders and the spine tilts accordingly.

When the carvings are boxed and a centerline splits the box, one can readily see the tilt of the head and the slanting of the shoulders, hips, and knees.

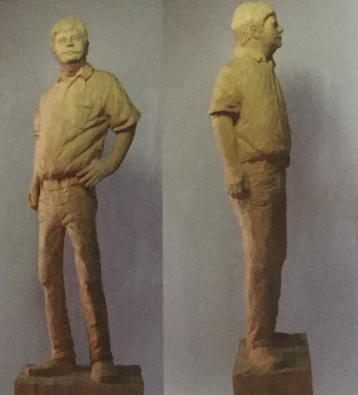

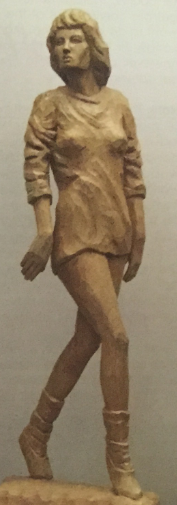

By contrast, none of the planes of this figure are paralel to the original block of wood.

This standing figure Is in the block. All the planes of the carving are parallel to the original block of wood

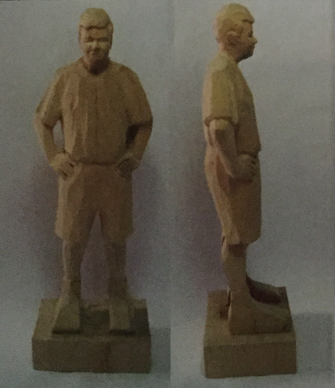

Caricatures, too, can be In the block like this one carving are parallel to the original block of wood.

Or they can be out of the block like this one, carved by Marv Kaisersatt.

The fact that it is out of the block gives this carving of a dancer a sense of movement. Here, none of the planes of the figure are parallel with the original block of wood.

In this horse carving, movement is suggested by the turning of the head and the tail, taking it out of the block too.

Of course, there is no law that dictates that we must get our carvings out of the block. In art, anything you want to do is fair game. Many fine sculptures are intentionally in the block. It is something we can consider, however, as we work to create interest and variety in our carvings.

Note: The use of the bandsaw to cut away waste wood all around the figure contributes to the tendency to leave carvings in the block, since all the cuts that a bandsaw makes are parallel to those of the block of wood.

For this reason, the traditional carvers I’ve worked with and observed did not saw away wood from either the front or back of the figure. They carved "in from the front,” establishing the posture there first and then orienting the back to the front.

This allowed them to turn the head, move the shoulders, and turn the figure however they wanted; because they had not already cut away the wood, they needed to accomplish that. I used that technique in carving the turned figures in the examples here.